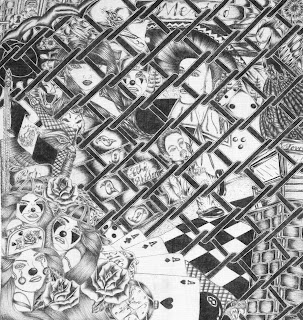

Handkerchief Drawings by Hispanic Inmates in Texas Prisons

A Collection and Essay by Ed Jordan

Paño — Spanish for "cloth" or

"handkerchief," specifically one illustrated with ballpoint pen

and/or colored pencil. Paños are also referred to as pañuelos, and

one of my artists called them pasajes, or

"passages." These are a popular form of Chicano prison

illustration and are a variation of the decorated #10 envelope that originated

in Southwest prisons in the early 20th century.

Paño — Spanish for "cloth" or

"handkerchief," specifically one illustrated with ballpoint pen

and/or colored pencil. Paños are also referred to as pañuelos, and

one of my artists called them pasajes, or

"passages." These are a popular form of Chicano prison

illustration and are a variation of the decorated #10 envelope that originated

in Southwest prisons in the early 20th century.

Designs with ballpoint

pens on white handkerchiefs that the inmate has to purchase from the prison

commissary are often highly detailed and complex illustrations that tell

the inmate's story or visions in art, rather than words. As the Mexican culture

is a visual culture for the most part, the paño prison art

styles and techniques are passed down from prisoner to prisoner. In the

case of the ever-popular Virgen de Guadalupe image, often a stencil is

made and passed on or sold to another inmate. One of these I have seen has probably

been used by several inmates to copy onto a handkerchief. The Disney characters

are also copied this way and then personalized by the artist and sent to a

beloved child.

Much like the images

used by the Kuna Indians of Panama, the paño images are from

calendars, magazines, tattoos, and a variety of other sources. They are

traced onto the cloth and drawn with ballpoint pens, then often colored with

colored pencils. Sometimes if the artist lacks colored

pencils, the paños are stained and colored with coffee,

wax crayons, shoe polish, felt-tip markers, or whatever else might be

available. One artist had a great time with a lipstick, probably stolen

from a female employee of that prison.

The commissary

handkerchiefs are the most popular cloths to use, but if the inmate cannot

afford them, bed sheets and pillow cases of similar texture are used. Please

note the painstaking work on several of these examples that

have fringes made one after another by hand, and then consider the time

this must have taken.

The commissary

handkerchiefs are the most popular cloths to use, but if the inmate cannot

afford them, bed sheets and pillow cases of similar texture are used. Please

note the painstaking work on several of these examples that

have fringes made one after another by hand, and then consider the time

this must have taken.

As a collector of this

art form, I was told many times by the inmate artist that the paño I

was expecting to receive had been confiscated in one of the many prison

security crackdowns or raids. The guards would have instructions to raid the

cells, and almost all materials found would be taken and destroyed as the

prison employees searched for illegal contraband.

As the art form has

become more popular, the art has often become more sophisticated, and

the talent inherent in many of the inmates has resulted in some amazing

renderings. Many of the artists started signing their work, and museums, folk

art collectors, and galleries have started collecting them.

I did not start

collecting paños until about 1994. After graduating with a

B.F.A. from The University of Texas and a tour of Europe with the U.S. Army, I

ended up in Dallas and became the art director of an advertising agency

associated with the American Association of Advertising Agencies, where I

handled the advertising for the State Fair of Texas and its many smaller

entities in the 1960s and '70s. While serving as a design director and

troubleshooter for a national packaging firm, I later participated in many art

fairs, as well as nationwide museum and gallery shows (including 25 years exhibiting

at the fabled Laguna Gloria Fiesta). In the summer of 1988, Blinn

College of Brenham called to ask me to become the art instructor at their

"Bastrop Campus," which they admitted was within the Federal

Correctional Institution outside that city. Their current instructor was

leaving for another position.

While teaching, I

became aware of a new art form for me, the paño. Since I was

forbidden to take anything in or out of the prison, it was only after the

school closed down several years later that I was able to begin building this

collection. I contacted one of my former students, Paul Young, who was by then

finishing a term in a Texas prison, and asked him to look for paños for

me. In addition to this collection of paños, I also amassed a

large collection of Mexican folk art. Paul is responsible for most of my

collection and found my best artist, Ruben Magallon, whose many paños you

will see in this exhibit. I would have asked Paul and Ruben to be here to

share credit for this wonderful art form and their work, but Paul died

recently, and Ruben disappeared after his release from prison.

Paños/Pañuelos is on display at Texas Folklife Gallery

August 1 - October 25, 2013

Opening Reception - Sunday, August 18, 2:00 to 4:00 PM

Commentary by Ed Jordan and Refreshments: free and open to the public